Working-class homeowners in Pueblo, Colorado have struggled to keep up with their sky-high electric bills. Locals said rampant shutoffs have plunged entire city blocks into darkness and sent power-starved families to motels and homeless shelters. Senior citizens have given up television and unscrewed refrigerator lights in an attempt to save money. And local businesses have grappled with electric bills as high as their rents.

Frustrated by bloated power bills and frequent shutoffs, citizens of Pueblo have lobbied the city council to abandon natural gas and switch to more affordable renewable energy.

By organizing concerned citizens and packing town halls, Pueblo’s Energy Future managed to push the city council to pass a resolution committing to generate 100 percent of the city’s power from renewables by 2035. Based on the cost of electricity from utility-scale wind farms in the region, ratepayers could save money by switching to clean energy.

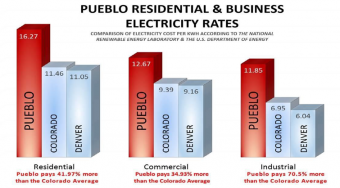

“When people lose their electricity, they lose their houses,” said Anne Stattelman, director of Posada, an organization providing housing to homeless families in Pueblo County. Pueblo is one of Colorado’s poorest cities but has one of the highest electricity rates in the state, she said.

It’s often taken for granted, but nearly every facet of modern life depends on electricity. When the power goes off, refrigerators full of food go to waste. Children cannot take hot showers or do their homework. Parents have to choose between dinner, medicine or keeping the lights on.

Stattelman recalled one woman, who, after losing power, came to a shelter with a child in need of 24-hour care. The local utility, Black Hills Energy, charged a $400 reconnection fee.

Black Hills acquired the region’s previous utility company in 2008 and received authorization for a new $72 million gas-fired power plant. The company raised rates to cover the costs and installed smart meters in low-income neighborhoods, a move that makes it easier to shut off power remotely. In 2015, the utility disconnected more than 6,000 households in Pueblo, a city of roughly 43,000 households.

“Most people that live here, have lived here for a while and they see how the rate hike has affected them,” said Rebecca Vigil, the community coordinator for Pueblo’s Energy Future, an organization dedicated to advancing clean energy in Pueblo.

“I’ve seen how this has affected my city,” Vigil said. “For the past six to eight years, there’s been a definite blight.”

Now, citizens are urging the city to exit its agreement with Black Hills Energy in 2020. They want to form a municipal electric utility, putting the city in charge of power generation. A municipal utility can purchase electricity on the open market or generate its own. Pueblo would not be required to purchase the natural gas plant from Black Hills Energy.

“We want the community to come together and feel comfortable saying what they want and expect from their utility,” Vigil said. “They want a secure, clean, affordable and just energy future for Pueblo.”

Because the price of natural gas fluctuates, ratepayers may see their bills grow larger when fuel costs spike. Wind and solar promise stable costs.

“Renewables are consistent. They don’t have the same volatility, so people can plan,” said Stattelman, who wants the city to move to renewable power, both to lower bills and create jobs.

Pueblo, known to locals as the “Pittsburgh of the West,” has lost thousands of steel jobs in recent decades. Now Vestas, one of the largest wind turbine manufacturers in the country, operates a plant in Pueblo that employs 600 people. Rooftop solar installations could add even more jobs while taking advantage the region’s consistently sunny weather—Colorado enjoys more sunshine than all but a few states.

“We don’t want to be known as steel city,” Stattelman said, “We want to be sun city.”

Source: ecowatch.com