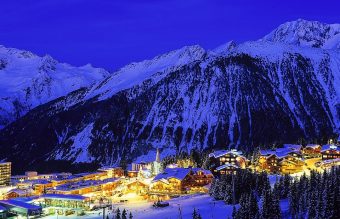

For the tourists thronging the streets and pavement cafes of Chamonix, the neck-craning view of Mont Blanc, the highest mountain in the Alps, is as dazzling as ever.

But the mountaineers who climb among the snowy peaks know that it is far from business as usual – due to a warming climate, the familiar landscape is rapidly changing.

“Global climate change has serious and directly observable consequences in high mountains,” says Vincent Neirinck from Mountain Wilderness, a campaign group that works to preserve mountain environments around the world.

One of the consequences of climate change is the ongoing retreat of glaciers.

“In the Alps, the glacier surfaces have shrunk by half between 1900 and 2012 with a strong acceleration of the melting processes since the 1980s,” says Jacques Mourey, a climber and scientist who is researching the impact of climate change on the mountains above Chamonix.

The most dramatic demonstration of glacial retreat is shown by the Mer de Glace, the biggest glacier in France and one of Chamonix’s biggest tourist hotspots which would now be unrecognisable to the Edwardian tourists who first flocked there.

“The Mer de Glace is now melting at the rate of around 40 metres a year and has lost 80m in depth over the last 20 years alone,” says glaciologist Luc Moreau.

A stark consequence of the melting Mer de Glace is that 100m of ladders have now been bolted onto the newly exposed vertical rock walls for mountaineers to climb down onto the glacier.

Another key impact of climate change in the mountains is that it is leading to an increase in the number of rockfalls; more than 550 occurred in the Mont Blanc massif alone between 2007 and 2015.

The reason, explains Mourey, is that the permafrost that lies within cracks of rocks and cements them together is now melting.

“As the permafrost melts, whole sections of rock become destabilised and more prone to collapse.”

This is what caused the destruction of the iconic Bonatti pillar, a massive column of rock and popular climbing spot that collapsed in the scorching hot summer of 2005. Significantly, climate change is happening almost twice as fast in high mountains as compared to the rest of the planet.

“Whilst there are many theories as to why this is happening, we don’t fully understand what’s going on,” says Mourey. What is not disputed, though, is that many climbing routes have been drastically altered by climate change.

“A 1970s climbing and mountaineering guidebook to the 100 best routes around Mont Blanc isn’t useable any more as most of the routes have changed and can’t be used,” he says.

The trails to the high mountain huts around Mont Blanc which are used by climbers are becoming more dangerous too, forcing the authorities to adapt and take action.

In 2012 the trail to the Conscrits hut was judged to have become too dangerous following increasing numbers of rockfalls, so a 60m Himalayan-style suspension bridge was built to make access to the hut safer.

A completely new trail, including the installation of fixed ladders, has recently had to be built to the Charpoua hut following the melting of glaciers which made the previous trail too difficult and dangerous.

Given Chamonix’s status as the cradle of modern mountaineering and alpine pursuits, the authorities are now making a determined effort to adapt to these changing conditions to ensure that climbing can continue.

“We want to support the idea that alpinism and its values are not dead and we must keep on climbing safely,” says Claude Jacot, a Chamonix councillor and head of mountain safety for the region.

But for some, the area is already becoming too dangerous.

“This year we’ve deliberately reduced our programmes on Mont Blanc due to the increased rockfall caused by higher temperatures over the last few years,” says Ed Chard from trekking operator Jagged Globe.

So what will happen to climbing around Chamonix in the coming years? Mourey is optimistic that the sport still has a future in the Alps, but future mountaineers will have to adapt.

“You’ll still be able to climb in the future – you’ll just have to change the way you climb,” he says. “If anyone doesn’t believe that climate change exists, they should come to Chamonix to see it for themselves.”

Source: Guardian