Vestas chief Runevad says UK rules shut out the latest hi-tech turbines, leaving Britain behind as the global wind boom spreads. The world’s biggest producer of wind turbines has accused Britain of obstructing use of new technology that can slash costs, preventing the wind industry from offering one of the cheapest forms of energy without subsidies. Anders Runevad, chief executive of Vestas Wind Systems, said his company’s wind turbines can compete onshore against any other source of energy in the UK without need for state support, but only if the Government sweeps away impediments to a free market. While he stopped short of rebuking the Conservatives for kowtowing to ‘Nimbyism’, the wind industry is angry that ministers are changing the rules in an erratic fashion and imposing guidelines that effectively freeze development of onshore wind. “We can compete in a market-based system in onshore wind and we are happy to take on the challenge, so long as we are able to use our latest technology,” he told the Daily Telegraph.

Vestas chief Runevad says UK rules shut out the latest hi-tech turbines, leaving Britain behind as the global wind boom spreads. The world’s biggest producer of wind turbines has accused Britain of obstructing use of new technology that can slash costs, preventing the wind industry from offering one of the cheapest forms of energy without subsidies. Anders Runevad, chief executive of Vestas Wind Systems, said his company’s wind turbines can compete onshore against any other source of energy in the UK without need for state support, but only if the Government sweeps away impediments to a free market. While he stopped short of rebuking the Conservatives for kowtowing to ‘Nimbyism’, the wind industry is angry that ministers are changing the rules in an erratic fashion and imposing guidelines that effectively freeze development of onshore wind. “We can compete in a market-based system in onshore wind and we are happy to take on the challenge, so long as we are able to use our latest technology,” he told the Daily Telegraph.

“The UK has a tip-height restriction of 125 meters and this is cumbersome. Our new generation is well above that,” he said. Vestas is the UK’s market leader in onshore wind. Its latest models top 140 meters, towering over St Paul’s Cathedral. They capture more of the wind current and have bigger rotors that radically change the economics of wind power. “Over the last twenty years costs have come down by 80pc. They have come down by 50pc in the US since 2009,” said Mr Runevad. Half of all new turbines in Sweden are between 170 and 200 meters, while the latest projects in Germany average 165 meters. “Such limits mean the UK is being left behind in international markets,” said a ‘taskforce report’ by Renewable UK. The new technology has complex electronics, feeding ‘smart data’ from sensors back to a central computer system. They have better gear boxes and hi-tech blades that raise yield and lower noise. The industry has learned the art of siting turbines, and controlling turbulence and sheer. Economies of scale have done the rest. This is why average purchase prices for wind power in the US have fallen to the once unthinkable level of 2.35 cents per kilowatt/hour (KWh), according to the US energy Department.

“The UK has a tip-height restriction of 125 meters and this is cumbersome. Our new generation is well above that,” he said. Vestas is the UK’s market leader in onshore wind. Its latest models top 140 meters, towering over St Paul’s Cathedral. They capture more of the wind current and have bigger rotors that radically change the economics of wind power. “Over the last twenty years costs have come down by 80pc. They have come down by 50pc in the US since 2009,” said Mr Runevad. Half of all new turbines in Sweden are between 170 and 200 meters, while the latest projects in Germany average 165 meters. “Such limits mean the UK is being left behind in international markets,” said a ‘taskforce report’ by Renewable UK. The new technology has complex electronics, feeding ‘smart data’ from sensors back to a central computer system. They have better gear boxes and hi-tech blades that raise yield and lower noise. The industry has learned the art of siting turbines, and controlling turbulence and sheer. Economies of scale have done the rest. This is why average purchase prices for wind power in the US have fallen to the once unthinkable level of 2.35 cents per kilowatt/hour (KWh), according to the US energy Department.

At this level wind competes toe-to-toe with coal or gas, even without a carbon tax, an increasingly likely prospect in the 2020s following the COP21 climate deal in Paris. American Electric Power in Oklahoma tripled its demand for local wind power last year simply because the bids came in so low. “We estimate that onshore wind is either the cheapest or close to being the cheapest source of energy in most regions globally,” said Bank of America in a report last month. A study by Bloomberg New Energy Finance concluded that the global average for the ‘leveled cost of electricity’ (LCOE) for onshore wind fell to $83 per megawatt/hour last year compared to $76-$82 for gas turbine plants in the US, or $85-$93 in Asia, or $103-$118 in Europe. Yet the size of the new wind turbines is precisely the problem in Britain, though the industry says they are less intrusive than more numerous smaller towers. Rural activists vehemently oppose further onshore expansion for a mix of reasons, often to protect the countryside and migrating birds. One application was turned down on fears that blade-noise would startle race-horses. It is understood that up 100 backbench Tory MPs wish to stop development of onshore wind altogether and that is effectively now happening. While there is no fixed height limit, the guidelines for local governments imply a 125 meter cap. This is often beaten down to nearer 100 meters, and the planning obstacles have become a nightmare for the industry.

At this level wind competes toe-to-toe with coal or gas, even without a carbon tax, an increasingly likely prospect in the 2020s following the COP21 climate deal in Paris. American Electric Power in Oklahoma tripled its demand for local wind power last year simply because the bids came in so low. “We estimate that onshore wind is either the cheapest or close to being the cheapest source of energy in most regions globally,” said Bank of America in a report last month. A study by Bloomberg New Energy Finance concluded that the global average for the ‘leveled cost of electricity’ (LCOE) for onshore wind fell to $83 per megawatt/hour last year compared to $76-$82 for gas turbine plants in the US, or $85-$93 in Asia, or $103-$118 in Europe. Yet the size of the new wind turbines is precisely the problem in Britain, though the industry says they are less intrusive than more numerous smaller towers. Rural activists vehemently oppose further onshore expansion for a mix of reasons, often to protect the countryside and migrating birds. One application was turned down on fears that blade-noise would startle race-horses. It is understood that up 100 backbench Tory MPs wish to stop development of onshore wind altogether and that is effectively now happening. While there is no fixed height limit, the guidelines for local governments imply a 125 meter cap. This is often beaten down to nearer 100 meters, and the planning obstacles have become a nightmare for the industry.

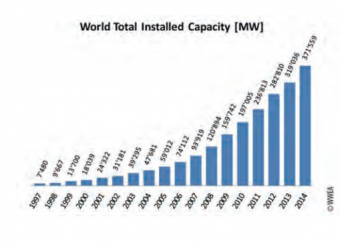

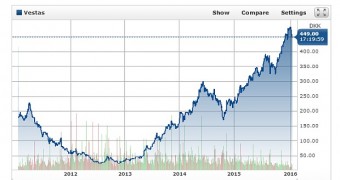

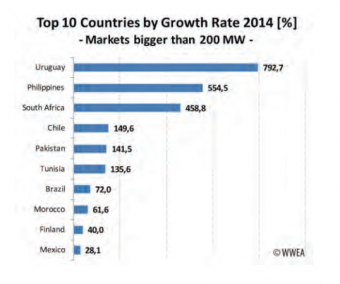

Amber Rudd, Secretary of Energy and Climate Change, drastically revised policy last year, announcing that support for onshore wind would be cut from April 2016. She said 250 wind farms in the planning phase were unlikely to be built as a result but insisted that Britain was “reaching the limits of what is affordable, and what the public is prepared to accept”. Mr Runevad has other fish to fry in a booming global wind market. The Vestas share price has soared twentyfold since 2012, when the company flirted with bankruptcy after a debt-driven expansion, and faced cu At the time, critics said the wind bubble had played itself out, but the epitaphs were premature. The company’s plant in the Isle of Wight producing blades – shut in the crisis – has opened again. Vestas has raised its revenue guidance for this year to a record €8bn to €8.5bn, with a profit margin (EBITDA) of 9pc to 10pc. It has a mounting backlog of orders for South Korea, China, Brazil, India, Turkey, the US, Finland, and Greece. The world added a record 51 gigawatts (GW) of wind power capacity last year. Almost 40pc of this was in China, where the vast plains of the “three Norths’ have become the epicentre of the global industry – though the US midwest from the Dakotas to Iowa and Texas is no slouch either.

Amber Rudd, Secretary of Energy and Climate Change, drastically revised policy last year, announcing that support for onshore wind would be cut from April 2016. She said 250 wind farms in the planning phase were unlikely to be built as a result but insisted that Britain was “reaching the limits of what is affordable, and what the public is prepared to accept”. Mr Runevad has other fish to fry in a booming global wind market. The Vestas share price has soared twentyfold since 2012, when the company flirted with bankruptcy after a debt-driven expansion, and faced cu At the time, critics said the wind bubble had played itself out, but the epitaphs were premature. The company’s plant in the Isle of Wight producing blades – shut in the crisis – has opened again. Vestas has raised its revenue guidance for this year to a record €8bn to €8.5bn, with a profit margin (EBITDA) of 9pc to 10pc. It has a mounting backlog of orders for South Korea, China, Brazil, India, Turkey, the US, Finland, and Greece. The world added a record 51 gigawatts (GW) of wind power capacity last year. Almost 40pc of this was in China, where the vast plains of the “three Norths’ have become the epicentre of the global industry – though the US midwest from the Dakotas to Iowa and Texas is no slouch either.

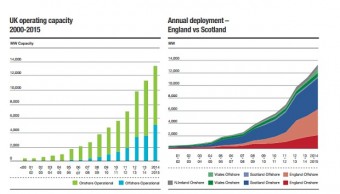

Global capacity is 370 GW, three and a half times Britain’s entire electricity market. A ‘roadmap’ study by the International Energy Agency suggested that China’s wind power capacity could reach 200 GW by 2020, 400 GW by 2030, and 1000 GW by 2050, a staggering sum. “As technology improves, there are no insurmountable barriers to realising these ambitious targets,” it said. t-throat competition from Britain has 8.5 GW of onshore wind capacity and 5 GW of offshore. Wind accounted for 11pc of the country’s electricity last year, reaching a record 17pc in December. The UK still makes up half the world’s offshore wind power, taking advantage of shallow banks that keep costs down. The Government is backing further expansion, expected to reach a total capacity of 11 GW by 2020. Yet this is far more expensive than onshore and requires the sorts of subsidies needed for the nuclear industry, though cost is not the only factor. Wind has merits for energy security and the balance of trade. What seems likely is that the era of onshore wind growth in Britain is coming to an end for political reasons just as the technology comes of age and finally makes sense on a commercial basis. It is a policy paradox.

Britain has 8.5 GW of onshore wind capacity and 5 GW of offshore. Wind accounted for 11pc of the country’s electricity last year, reaching a record 17pc in December. The UK still makes up half the world’s offshore wind power, taking advantage of shallow banks that keep costs down. The Government is backing further expansion, expected to reach a total capacity of 11 GW by 2020. Yet this is far more expensive than onshore and requires the sorts of subsidies needed for the nuclear industry, though cost is not the only factor. Wind has merits for energy security and the balance of trade. What seems likely is that the era of onshore wind growth in Britain is coming to an end for political reasons just as the technology comes of age and finally makes sense on a commercial basis. It is a policy paradox.

Source: www.telegraph.co.uk