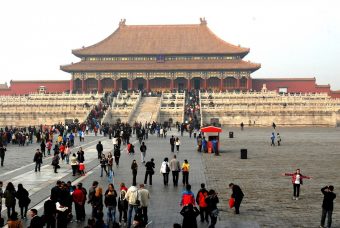

More than one million people die each year in China from particulate matter air pollution, but despite 15 years and billions of dollars of efforts to clean up the country’s air, dangerous winter smog persists.

Now, an international team of scientists think they have discovered the reason why: The instruments used to measure Beijing’s particulate matter pollution were misinterpreting their readings.

“Our research points towards ways that can more quickly clean up air pollution. It could help save millions of lives and guide billions of dollars of investment in air pollution reductions,” said Jonathan M. Moch, first paper author and graduate student at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences(SEAS), in a Harvard press release.

In the past, instruments had picked up on the high level of sulfur compounds and read them as sulfates. The Chinese government therefore focused on reducing sulfur dioxide pollution from coal burning power plants. But while the government was successful in those efforts, the overall air pollution levels did not decrease as expected.

That is because, as the team of researchers from Harvard, Tsinghua University and the Harbin Institute of Technology revealed in Geophysical Research Letters Thursday, a lot of those sulfur compounds were actually hydroxymethane sulfonate (HMS)—a compound formed when sulfur dioxide reacts with formaldehyde in smog or fog. The type of instruments used to measure particulate matter in Beijing can easily confuse the two.

The researchers ran a computer model and found that HMS compounds could make up a lot of the particulate matter found in China’s persistent winter smog.

“By including this overlooked chemistry in air quality models, we can explain why the number of wintertime extremely polluted days in Beijing did not improve between 2013 and January 2017 despite major success in reducing sulfur dioxide,” Moch said.

Moch also said the findings explained why the government’s efforts finally seemed to pay off last winter—sulfur dioxide fell below formaldehyde for the first time, so less HMS was formed.

“We think there could have been a shorter way if they had gone straight at formaldehyde,” Moch told The Boston Globe.

Major sources of formaldehyde pollution in Eastern China include emissions from vehicles and chemical or oil refineries, so the researchers recommend that China now work on reducing pollution from these sources.

The research team now plans to directly measure HMS levels in Beijing using altered instruments and to use models to assess the importance of HMS formation to pollution across China.