The Watt-r wants to offer a motorized, sustainable solution to the long journeys many African women have to take to carry water back home.

Jose Paris used to design cars for a living. His next vehicle, though, is different: It doesn’t have a steering wheel or brakes or doors, and instead of carrying people, its sole purpose is to carry water, powered by a canopy of solar panels.

The design, called Watt-r, aims at reducing the time that women and children spend collecting water in places like rural Africa. On average, a trip to get water in a developing country requires walking more than three miles round-trip, carrying a jug that weighs around 40 pounds on the way back. In areas affected by drought, the walk can be 15 miles or more.

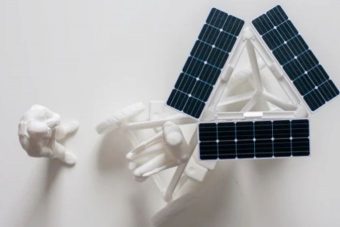

The simple new cart, still in development, will likely carry a dozen 20-liter containers of water at a time, as an entrepreneur walks next to it. Solar power, not human power, will propel it forward. Instead of an engine, it will use a 150-watt electric bike motor, controlled with a simple throttle and tiller. When the entrepreneur stops in a village or city to sell the water, the cart can also double as a charging station for mobile phones or other small electronics.

The minimal design makes it cheap to produce. “I’ve always been interested in frugal innovation,” Paris says. He first began thinking about the concept nearly a decade ago, but at the time, solar panels were much more expensive. Those costs have dropped dramatically, and 3D printing has made some other parts inexpensive to produce as well. The simplicity of the structure is also key to the low cost.

The bike is designed only to travel at walking speed, in relatively flat areas, so it needs less power. The electric bike motor will run, Paris says, as long as the sun is shining; because the target market is areas near the equator, there is ample sun most of the year. It doesn’t have batteries and doesn’t run at night, but people typically don’t gather water at night for security reasons.

“It would be very easy to think about an autonomous version, for instance, or to think about installing more power or adding batteries,” he says. “This mission creep is something that I’m very used to after working so many years in the car industry–it’s very typical, somebody always has something else to add. This is an exercise in really paring everything down as much possible and being very conscious of it.”

He estimates that an entrepreneur making daily micro-payments on the cart would be able to pay it off in three years. The cart would fit into an existing system of vendors selling water, both in cities and in rural areas. “There’s a market already, and people are paying for this service,” he says. “If you go to Nairobi, there’s enormous kiosks everywhere where they’re selling jerry cans because the water distribution is so unreliable.”

In some cases, water is currently delivered by bike or pushcarts–but that work is done by men because of the physical strength required. The solar-powered cart could also be used by women, who aren’t currently paid for their daily trips.

Paris, who lives in London, plans to test a rough prototype locally or in Spain, and then bring a version to Kenya for more testing in early 2018. If people there want more features–the solar power, for example, could also be used to run a water purification system–the design will evolve.

He sees the design as fitting into an underused category of transportation. “When you look at these developing countries, there seems to be this idea that people just walk, and then they graduate to a Toyota pickup truck . . . in my mind, there’s quite a lot of room in the middle,” he says. “A lot of innovation can happen in those forgotten spaces, that we have forgotten in the West for 120 years, but for them, is crucial. The key thing is now you can add just a little bit of 21st-century technology, and all of the sudden, something from the 19th century becomes super modern.”

Source: fastcompany.com